Ruled by the Habsburg monarchy, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was the largest political entity in mainland Europe before World War I. Rising pro-Slav nationalism in the empire was a threat to it and it was supported the free Slav state of Serbia. The assassination of Austro-Hungarian crown prince and heir apparent Franz Ferdinand by a Bosnian Serb gave Austria-Hungary a pretext to declare war on Serbia on 28th July 1914. The conflict escalated in a few weeks with all the major European powers taking sides; and thus World War I began. Austria-Hungary suffered initial defeats in the war as its invasion of Serbia was thwarted. However, in 1915, a combined force of the Axis powers was able to invade Serbia. The internal turmoil in Austria-Hungary, primarily due to the numerous ethno-language groups in the empire, intensified during WW1 and this ultimately led to the disintegration of the empire. Here is a detailed analysis of Austria-Hungary’s participation in World War I including all the major events in which it was involved.

Dual Monarchy and Multi Ethnic Challenges

Formed in 1867 by a compromise agreement between Austria and Hungary, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was ruled by the Habsburg monarchy and was the largest political entity in mainland Europe before World War I. The Austrian and the Hungarian states were co-equal in this dual monarchic system, and had separate parliaments and governments. The imperial government under the Emperor, the two prime ministers, military representatives and a selected few oversaw the foreign affairs, joint finance and the military. Franz Josef was the first sovereign of the empire, crowned as king of both Austria and Hungary. His long reign extended well into WW1 till 1916.

The rise of nationalism in the 19th and early 20th century was a threat to old monarchic systems, which were slowly fragmenting and crumbling with time. This was more of a challenge for heterogeneous empires like Austria-Hungary, which had eleven major ethno-language groups scattered across the empire. They could be classified in two groups: the “ruling nations” including Germans and Hungarians, and the “ruled nations”: Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Vlachs (Romanians), Croats, Serbs, Slovenians and Italians.

The emergence of new nations in the neighboring Balkan regions, weakening of the Ottomans and political interest of powerful enemies in supporting nationalistic groups were compounding the problems for Austria-Hungary. The monarchic ideas of expansion of territory with force and subjugation were in conflict with the rise of socialism and nationalism among the populace, giving rise to tension that was increasingly difficult to manage.

Sarajevo Assassination and Initiation of War

The rise of south Slav nationalism in the Balkans was a threat to Austria-Hungary. The pro Slavs aimed to unite the Slavic population of the Balkans into a single nation, which included territories that were part of Austria-Hungary or those that the Empire wanted for itself. The idea had the background political support of the Russians and was actively pursued by nationalists of the free Slav state of Serbia. On 28th June 1914, Serbian nationalists assassinated Austro-Hungarian crown prince and heir apparent Franz Ferdinand, and his wife in Sarajevo.

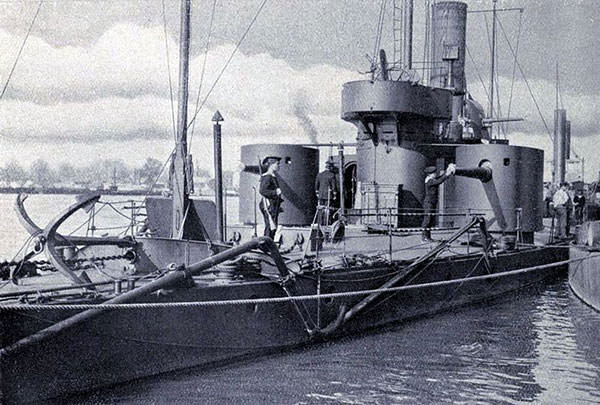

Austria-Hungary was angered but along with the event came the political opportunity to take punitive action on Serbia. After ensuring German support, a stern ultimatum with difficult conditions was handed over to Serbia on 23rd July 1914, with the aim of starting a war. On receiving an unsatisfactory reply on the 25th, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28th July 1914. The first blows were exchanged when the Serbians blew the railway bridge connecting the two countries and Austrian river patrolling ship SMS Bodrog, bombed the city of Belgrade. In 1914, the political, economic and territorial stakes were high among the Major Powers in Europe. Thus, within its first week the conflict pulled in the heavyweights, exponentially expanding the scope and scale of war; and thus the First World War began.

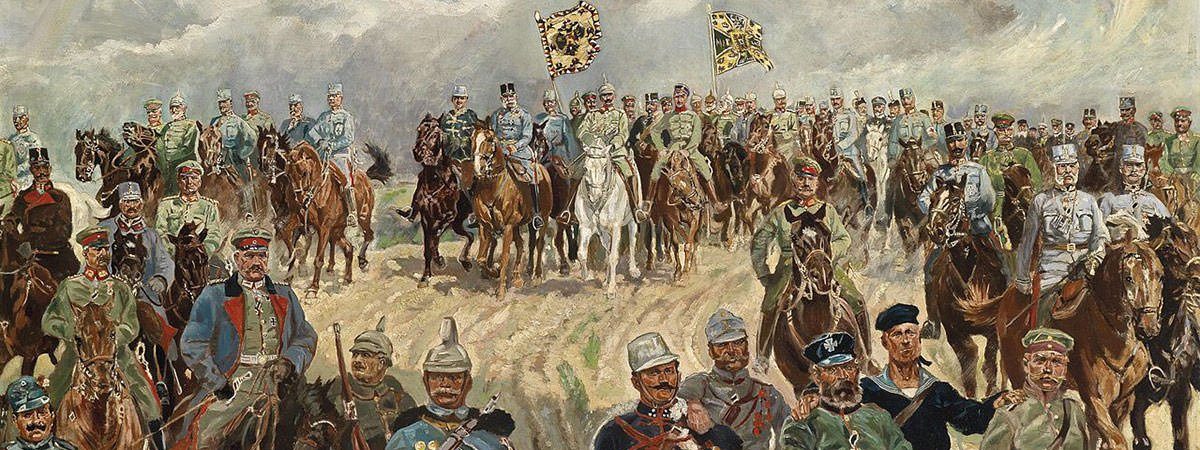

The Army and WWI

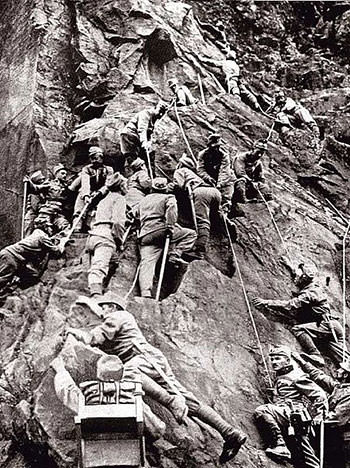

In the initial phase, large segments of the population supported the war and pro-war demonstrations were held in Vienna, Budapest and other cities of the empire. The imperial and royal army mobilized without any major issues during conscription, and were sent to the Serbian and Russian borders. Few weeks after the declaration of war in the autumn of 1914, the Austro Hungarians suffered a number of defeats against Serbian and Russian forces and had to retreat along a wide front. By December 1914, the fighting strength of the armed forces had deteriorated severely. The harsh weather and shortage of food supplies further deteriorated the spirit of the fighting units. And as the illusion of a short war dissipated, the war euphoria subsided and the attitude of civilian population changed significantly in the winter of 1914-15.

Further defeats in the spring of 1915 led to questions being raised on soldiers of Slav and other ethnic groups. This led to discord and served in the interest of nationalistic politicians of the empire. The situations improved over time with better training and opening of the Italian front in May 1915. Many predominantly Slav units were transferred to the Italian front, where most of them fought without problems until the end of the war. Success was finally seen in the joint Axis campaign against Serbia and Montenegro in the same year.

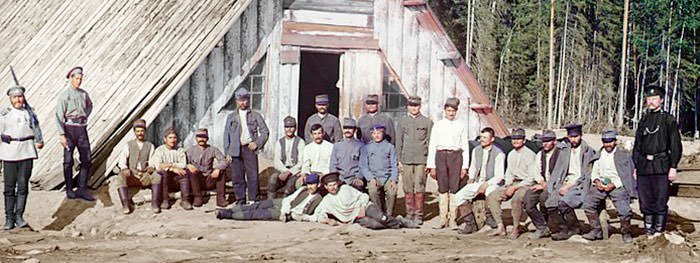

Mid-1916 onward the problem of deserters in the army was a concern, and in June the large scale Russian offensive forced them to retreat. Moreover, more than 380,000 Austro-Hungarian soldiers were held captive. The problems regarding ethnic populations remained an issue resurfacing from time to time, and was well exploited by the enemies of Austria-Hungary.

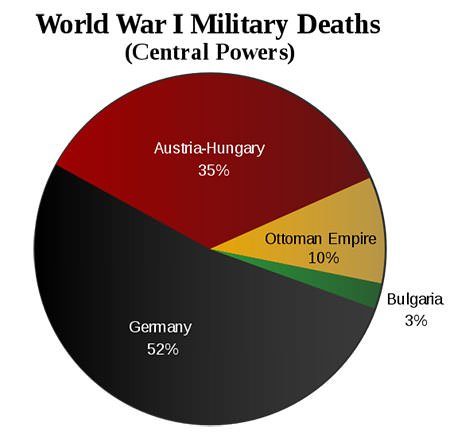

By late 1917, Russia exited from the war, and Austria-Hungary could concentrate on the Italian and French fronts. But, despite the morale boost, the long war had exhausted the troops and the Austro-Hungarian army was visibly falling apart by the middle of 1918. In October, Austrian forces were defeated on the Serbian front and on the Italian front leading to an armistice on November 3, 1918. In all, 1,495,200 Austro-Hungarian soldiers died during the Great War, including 480,000 that died as prisoners of war. Many more were injured.

Austrian Wartime Autocracy

Austrian Reichsrat (Parliament) in Vienna was closed by Chancellor Karl Von Stürgkh over the Bohemian question in March 1914. The assassination of the Archduke presented Stürgkh with a ready-made excuse to extend this autocracy and as the war broke out the parliament continued in a state of suspension. This was however not the case in Hungary, where the Reichstag in Budapest continued to meet throughout the war.

Freedom of assembly and of speech were restricted along with jury trials. Moreover. criminal cases were transferred to military tribunals. The imperial civil service was encouraged to carry out policing function against unruly elements who might oppose the preparation for war. The Army High Command was given the right to issue decrees involving vast areas of domestic policy; and to declare martial law if deemed necessary to protect military interests.

As the pressures of war mounted and it became clear that the conflict would be a long and arduous one, the restrictive measures mutated into harsh instruments of repressive control. Measures taken for the centralization of political decision-making became reasons for fragmentation between military and civilian authorities.

Death of Franz Joseph and Polarization

The last significant Habsburg monarch, remaining popular to the end of his life, Emperor Franz Josef died on 21 November 1916 after reigning for 66 years. He was succeeded by his grandnephew Karl I who in June 1917, reopened the Austrian parliament with the intent of mending the relationships among Austria-Hungary’s ethnic groups. This quickly turned into a disaster because it finally gave the representatives of the nationalities the chance to bring up all the disputes that had been glossed over for two years. Blacked out for 2 years the Czech, Polish and South Slav politicians vented their frustration and delivered statements justifying political independence, while Social Democrats joined with the Slavic parties in calling for political federalization.

The Entente powers had a keen eye on the political unrest in Austria-Hungary and consequently, Great Britain, France and the United States officially recognized the national committees formed by the anti-Habsburg activists in exile, allowing them to form provisional governments and promising them the independence of their peoples’ respective territories after the war.

Disintegration

By 1918, the seeds of political disintegration had grown in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Exhausted by a long war that their country seemed to be losing and political disagreements among the leaders created an inner conflict for many civilians and soldiers. As the situation turned critical and demands for the dissolution of the Hapsburg Monarchy grew Emperor Karl I published a manifesto in October 1918, granting all the nationalities full sovereignty within the boundaries of the Austrian state.

This last ditch effort for federalization and saving the monarchy and empire failed to yield the desired outcome. None of these bodies, including the German parties, accepted this interpretation of their status or purpose. Consequently, in the post war negotiations a few months later, the dual monarchy ended. Czechoslovakia gained independence; the old union between Austria and Hungary was broken up; Croatia and Slovenia joined Serbia in a new kingdom later known as Yugoslavia; Galicia joined the reestablished Polish state; while Trento and Istria joined Italy. Most of these territorial changes happened according to the wishes of the majority of the population.

About Austria-Hungary. The author refers to the Axis Powers which is WWII. They were the Central Powers