Great Britain was the reigning superpower in the world at the time World War I began. In the years leading to the war, Britain had formed military alliances with France and Russia in the Triple Entente. These three countries were the leading Allied nations in WW1 against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria. After German invasion of Belgium, Great Britain entered the war invoking the Treaty of London which required Britain to safeguard Belgium’s neutrality. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), the British Army sent to the Western Front, played a key role in the Allies halting the German march towards Paris. Moreover, the British naval blockade of Germany played an important contributing role in final German capitulation in November 1918. Here is a detailed analysis of Britain’s participation in World War I including all the major events in which it was involved.

The Reigning Superpower

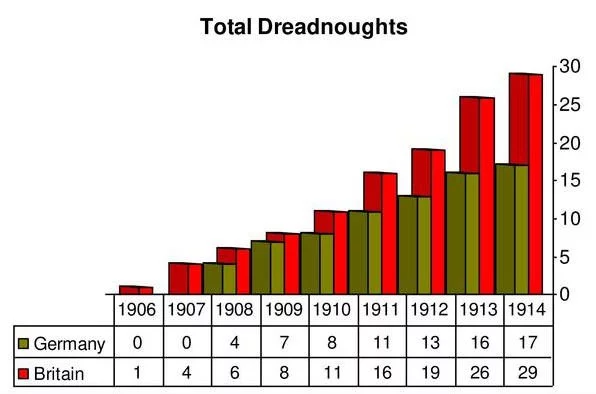

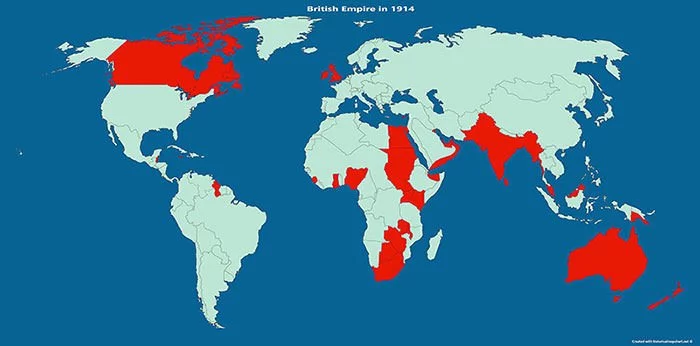

With a large colonial empire, a formidable naval force that helped it dominate the sea trades, and the fruits of industrial revolution, Great Britain had been the dominant world power for a couple of centuries. The quick and efficient rise of Germany in the decades leading to the War, was however a clear and perceived threat. The growing rivalry had witnessed a naval arms race and was among the reasons that Europe was looking for military alliances in a changing political climate.

In 1914, Britain was heavily industrialized with huge populations living in towns and cities. It was an economic superpower dominating trade and owning more than 40 percent of mercantile ships. It was culturally, socially and religiously more homogeneous than any other major power, and thus better placed to withstand the strains of war. And most importantly it had access to the resources and manpower of its large Colonial Empire, which meant that chances of winning a long war with Britain were bleak, though not impossible.

Entry Into WW1

As Europe got engaged in the July Crisis after the assassination of Austro Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Britain maintained a watchful eye. After war was declared, Germany put into action its Schlieffen Plan, which aimed at ending the French threat in a quick decisive conflict so that German forces could be transferred quickly to the Eastern Front to combat the much larger Russian army. With the aim of encircling France, Germany invaded neutral Belgium in early August 1914. The invasion invoked the decades old Treaty of London which required Britain among other Powers (including Prussia or Germany) to safeguard Belgium’s neutrality. This 1839 treaty was the official reason that was cited by Britain as it declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914. However there were other more important political, economic and military reasons that prompted British entry into war.

Britain was allied with France and Russia in the Triple Entente, but unlike the Franco-Russian alliance Britain was not bound militarily and was free to follow its own foreign policy. However German control of ports on the English Channel via France, Belgium and the Netherlands was against British interest. British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith wrote on August 2, 1914: “It is against British interests that France should be wiped out as a Great Power. We cannot allow Germany to use the Channel as a hostile base. We have to prevent Belgium being utilized and absorbed by Germany.” Moreover, the war threatened Asquith’s coalition government and his Liberal Party as top liberals threatened to resign if the cabinet refused to support France.

British foreign secretary and the main force behind the country’s foreign policy Sir Edward Grey warned against abandoning British allies. He opined that if Germany won the war, or the Entente won without British support, then, either way, Britain would be left without any friends and would be vulnerable to isolation.

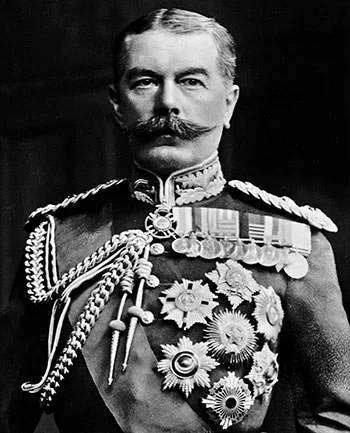

Kitchener’s Volunteer Army And Conscription

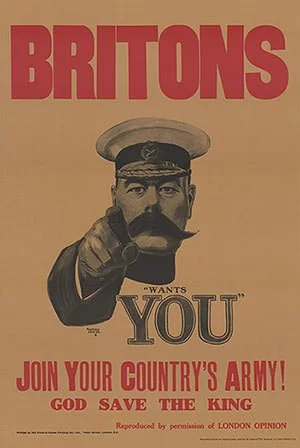

A day after Britain declared war on August 4, 1914, Herbert Kitchener was appointed the British Secretary of State for War. Against popular opinion that war would be over by Christmas, Kitchener predicted a long and brutal conflict and pressed for the expansion of the British Army by 500,000. The intention was to create a new army of volunteers, train it and make it ready to be put into action by mid-1916. However circumstances dictated its use before, and the first major action came in the Battle of Loos in September 1915.

A big and successful poster campaign was launched inviting men to join, and over twenty million recruitment pamphlets and leaflets were printed by April 1915. There was overwhelming response with 100,000 joining in the first 2 weeks. In places queues up to a mile long formed outside recruitment offices. The New Army, as it was officially called, was the biggest volunteer army the world had ever seen at the time, drawing almost 2.5 million men from August 1914 until March 1916. This was only eclipsed by the Indian Army in the Second World War.

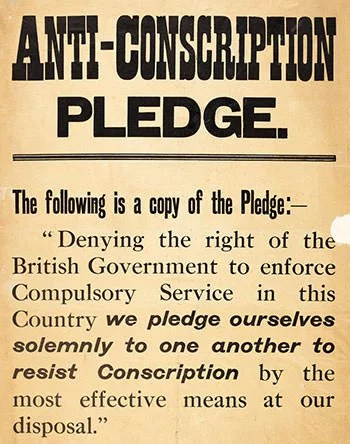

By the beginning of 1916, enthusiasm for volunteering plunged in Britain, as information about the horrors of the war began affecting the population, especially after Somme that claimed 500,000 lives. The government was thus forced to introduce conscription by way of the Military Service Acts. The Act specified that men from 18 to 41 years old were liable to be called up for service in the army barring some exceptions. It was introduced for the first time in January 1916 for single men, extended the liability to married men in May 1916 and further extended the upper age limit to 51 in 1918. Political reasons prevented the act for being imposed on Ireland but the terrible shortage of men in early 1918 led the British government to pass the act in Ireland. This led to the Conscription Crisis of 1918, which saw vigorous opposition to the act led by trade unions, Irish nationalist parties and Roman Catholic bishops and priests.

Defense of the Realm Act

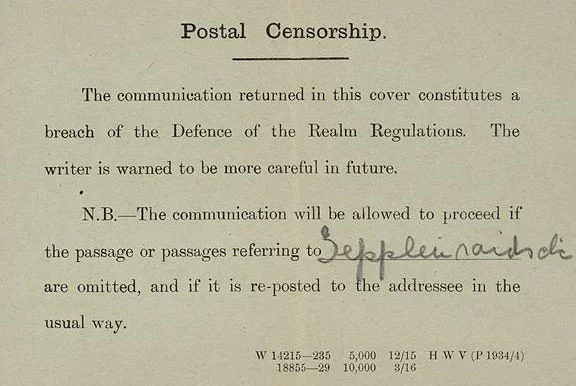

The House of Commons passed the Defense of the Realm Act within the first week of the British declaration of war. The act gave the government sweeping powers like requisition buildings or land needed for the war effort; or to make regulations creating criminal offenses. There were numerous social control measures adopted which included regulating alcohol consumption and food supplies. The legislation gave the government powers to suppress criticism, imprison without trial and to commandeer economic resources for the war effort. Any published information that was deemed to directly or indirectly benefit the enemy was punishable by law, as was any information likely to cause any conflict between the public and military forces. People who breached the regulations with intent to assist the enemy could be sentenced to death. Many antiwar activists were sent to prison and a small number of people were also executed under these wartime regulations.

Strains of War

With millions of young men joining the armed forces and the expansion of the war industry, Britain began to face labor shortages by early 1915. Government propaganda emphasized importance of women to the war effort, not just in a domestic role as supporters of their menfolk at war, but as positive contributors. An estimated 1 million moved from domestic service or other traditional women’s employment to take a wide variety of jobs including working in labor intensive areas like the munitions factories.

1915 was a tough year for the British; they did not win a single decisive battle on land or sea, and mostly suffered heavy defeats, like the one at the hands of the Ottomans at Gallipoli. The enthusiasm for volunteering was quickly subsiding and the pride of the nation Royal Navy was under pressure from German unrestricted submarine warfare campaigns. The failure on the war front brought about political change with the formation of a coalition government with the Unionists led by Asquith; Winston Churchill was removed from the Admiralty; and Kitchener’s authority was curtailed by the creation in May of a Ministry of Munitions under David Lloyd George. Britain had the luxury of its immense colonial resources but it had the burden of supporting its allies with money and equipment; and the financial burden was considered to be too great by some. The challenge was to win the war without crippling Great Britain’s post-war prosperity and position in the world, which was slowly being threatened by an emerging United States of America.

The Battle of Somme in 1916 saw 57,000 British casualties on its first day, and took many more British lives as it progressed over several months. Asquith was forced to resign and was replaced as prime minister by Lloyd George, but a decisive victory still eluded the British despite three major offensives in 1917. The year marked the greatest strain and division for the British home front. Industrial strikes began and the government had to take stronger punitive actions against dissenters; and anti-government and antiwar propaganda. The rising costs, lack of supplies and discontent among the public led to political and economic reforms, ranging from food rationing to an increased political franchise.

In April 1918 lack of fighting men led to the conscription being widened to all men aged eighteen to fifty-one. Legislation also allowed for extension of conscription to Ireland. This led to the Conscription Crisis of 1918 with vigorous opposition led by trade unions; Irish nationalist parties; and Roman Catholic bishops and priests. It galvanized support for political parties which advocated Irish separatism and influenced events in the lead-up to the Irish War of Independence.

British Expeditionary Force (BEF)

The British army before 1914 was comprised of just under 250,000 regulars, of whom nearly half were scattered across the Empire. Built with the purpose of defending the British Isles and policing the Empire, it was not an army intended to fight in a European war. The changing political situation and Britain’s treaty obligations to help France against a possible German attack however led to reforms and the formation of the BEF. After several military discussions with France, it was agreed upon that Britain would land a British Expeditionary Force of six infantry divisions in France in case of an attack. It was a force of close to 100,000 men.

As Britain declared war, four infantry divisions and one cavalry division of the BEF was dispatched to France almost immediately in August. The original BEF was however effectively destroyed by the end of 1914, suffering heavy casualty and losing many of its most experienced officers and men. Reinforcements arrived in the first winter from Territorial Force units; and divisions from India and Canada. The BEF was first reorganized on 26 December 1914 into two Armies, the First and Second. By mid-1915, it was Kitchener’s “New Army” which, despite not being fully trained, was forced into providing the reinforcements. The Third Army was formed in July 1915 with the influx of troops from Kitchener’s volunteers. After further reorganization, the Fourth Army and the Fifth Army were created in 1916. By now considerable forces from Australia, South Africa, New Zealand and Newfoundland had joined the battle. B.E.F. remained the official name of the British armies in France and Flanders throughout the First World War. At its peak, on 1 August 1917, the BEF in France and Belgium numbered 2,044,627 officers and soldiers.

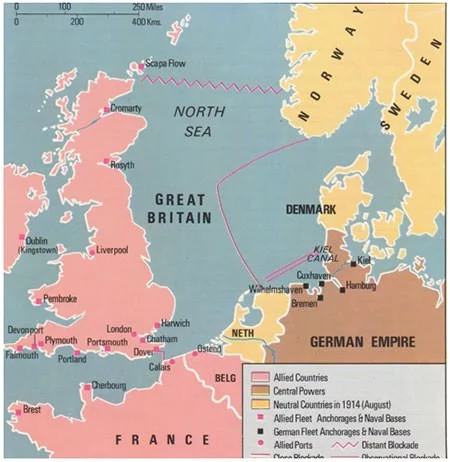

The British Naval Blockade

While Britain’s primary allies France and Russia possessed large armies suited for conducting land warfare, the same was not true for Britain which had only limited trained land forces. Britain was however a naval superpower and had considerable experience in carrying out naval warfare and executing naval strategies. The pre-war period of the early 20th century saw a naval arms race, as Germany began to grow its fleet to challenge Britain. Most historians agree that the planning for an economic blockade of Germany started in those times, and developed over the next decade to account for changing dynamics like development of German submarines and torpedo boats. The British had thus soon recognized that neutralizing the German navy from the outset, and preventing them from forming their own blockade of the United Kingdom, was the key to ensure their own survival and success in case of a conflict.

Britain established a naval blockade of Germany immediately on the outbreak of war in August 1914. The two entrances to the North Sea were blockaded along with the English Channel, and North Sea was declared as a war zone in November the same year. A long list of contraband items was issued that all but prohibited American trade with the Central powers.

The blockade was among United Kingdom’s greatest efforts during the war and was not just limited to the sea. Though carried out efficiently by the Royal Navy, it was administered and guided by the British Foreign Office. Political leaders made negotiations with neutral countries while spies and other ground assets were vital information sources that helped in sustaining the pressure on Germany as it tried to break free. Though the First World War was largely decided by forces in mainland Europe and Naval battles were only a handful, the impact of the British naval blockade of Germany (1914-1918) played an important contributing role in final German capitulation. It lasted well after the war was over in November 1918 and ended only after the Germans signed the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

Victory and Aftermath

Things began to take shape for the Allies after the failure of the German Spring Offensive of 1918. The 100 days Allied Offensive that followed, with the help of freshly arrived American troops, quickly changed the war as the strongest of the Central Powers, Germany, began retreating and facing defeat. The Central powers soon began signing armistice treaties, which ended with Germany on 11th November 1918, thus concluding the First World War.

Britain had entered the War with the aim of restricting Germany and the 1919 Versailles Peace Treaty ensured British goals. Geographically, the British Empire was, after the war, at its largest extent ever, if the League of Nations “trusteeships” are included. London took charge of an additional 1,800,000 square miles and 13 million new subjects; while Germany was left in shambles.

However, Britain incurred debts equivalent to 136% of its gross national product, and its major creditor, the USA, began to emerge as the world’s strongest economy. Foreign trade, a key part of the British economy, had been badly damaged by the war. Countries cut off from the supply of British goods had been forced to build up their own industries. Hence, they were no longer reliant on Britain. Britain’s enviable worldwide investments were wiped out; and its coal and cotton export markets had collapsed. By the late 1920s the white ‘dominions’ determined their own foreign policies and the Independence Movement began gaining ground in India. The years between the wars were the declining years for what had been the prominent imperial power of the world for close to 200 years.