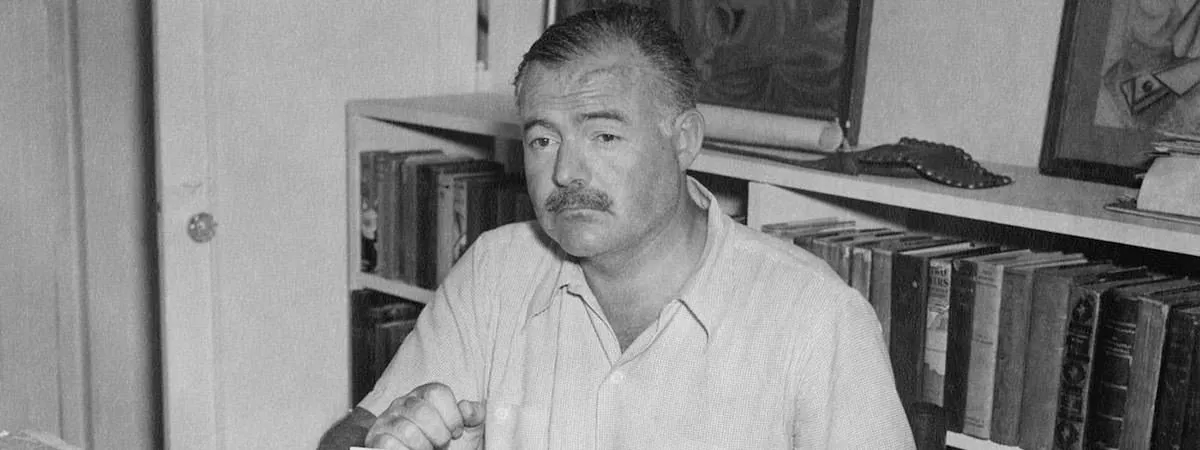

Ernest Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American author who is widely regarded as one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. He began his career as a journalist, wrote short stories for a while before publishing his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, in 1926. Active as a novelist for more than four decades, he received numerous awards including the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for Literature. Being a writer of such stature and fame in a country like the United States, Hemingway’s writings and style has been thoroughly praised, analyzed and criticized throughout his literary career and after his death in 1961. Apart from the various critiques of his works, noted books written in 1950’s by academicians like Carlos Baker, Charles Fenton and Philip Young determined the course of Hemingway studies for several years.

Hemingway began his journalistic career in 1917 at the age of 18, working as a cub reporter for the The Kansas City Star based in Kansas, Missouri. The style guidelines of the paper which advocated short sentences and paragraphs, positive writing and lack of slang were the early influences that guided his writings. In 1919 after recuperating from injuries he sustained in WWI, Hemingway became acquainted with Sherwood Anderson in Chicago and the two became friends. Almost 20 years Hemingway’s senior, Anderson was a published author of some repute and his realistic and non formulaic writing style would influence Hemingway in his early career (though Anderson would deny the same).

Hemingway moved to Paris in 1921 and his experiences in Europe over the next decade would have a major influence over developing him as an artist. These would include his expansive travels in the continent especially to the bullfighting festival in Spain, and his close association with the modernist expatriate writers based in Paris. Hemingway’s early non journalistic writings would be short stories published in works like In Our Time (1925) and Men Without Women (1927). His straightforward prose, his spare dialogue and his predilection for understatement are particularly effective in these works. According to biographer Carlos Baker the genre would help further develop the Hemingway distinct terse and lucid style, he would learn to “get the most from the least, how to prune language, how to multiply intensities and how to tell nothing but the truth in a way that allowed for telling more than the truth.”

Novels like the Son Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1929) established Hemingway as a writer and won him accolades from the critical circles. Hemingway’s first hand experience at the WWI and the postwar years in Europe formed the crux of these works, and his writings were described as “lean, hard, athletic, clean and masculine”. After exploring non fiction themes of bullfighting and his African safari, Hemingway produced his next notable work based on the Spanish Civil War with his 1940 novel For Whom the Bells Toll. The main characters of all these works were confident but sensitive young men scarred by the bitter experiences of the war torn world around them. To survive and succeed in such a world, one must conduct oneself with honor, courage, endurance and dignity; a set of rules identified as “the Hemingway code”, by noted Hemingway scholar Philip Young.

According to historian and literary critic Henry Louis Gates, Hemingway’s style was fundamentally shaped “in reaction to [his] experience of world war”. After World War I, he was the champion of the modernists who rebelled against the elaborate Victorian style of 19th-century writers and created a style “in which meaning is established through dialogue, through action, and silences—a fiction in which nothing crucial—or at least very little—is stated explicitly.” This narrative style brought to life the stories of individual lives in warfare and earned a wide readership. Hemingway saw war as complex, filled with moral ambiguities which offered unavoidable suffering.

The other major influence on Hemingway’s work may be attributed to his spirit of adventure and travel, along with his passion for hunting and bullfighting. His characters were often soldiers, hunters and bullfighters, at times primitive people whose courage and honesty are set against the brutal ways of modern society, and who in this confrontation lose hope and faith.

Hemingway himself liked to describe his style as the iceberg theory; where just like an iceberg the reader only sees the tip (or the story itself) but the much larger supporting structure and symbolism operate out of sight. In his essay “The Art of the Short Story”, Hemingway is clear about his method: “A few things I have found to be true. If you leave out important things or events that you know about, the story is strengthened. If you leave or skip something because you do not know it, the story will be worthless. The test of any story is how very good the stuff that you, not your editors, omit.” In his book Death in the Afternoon, he further elaborates his theory of omission “If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.”

In his paper Hemingway’s Camera Eye, researcher Zoe Trodd provided another interesting observation on Hemingway’s style. Building on the iceberg theory Trodd compares Hemingway’s writings to a “multi-focal” photographic reality; where static and short declarative sentences build something akin to a collage of images, and begin to make sense as a whole.

In 1952, Hemingway published his final masterpiece The Old Man And The Sea, a short novel about an old fisherman’s journey and his epic encounter with a giant fish. It is a stellar example of Hemingway’s realistic characters and sharp concise writing, woven in an inspiring tale about life, victory and defeat. The work would lead to his 1954 victory at the Nobel Prize “for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style.”

Ernest Hemingway passed away in 1961, leaving behind an impressive body of work. His distinct writing style born from the ashes of the First World War would however remain a noteworthy event in the history of English literature. Hemingway’s noticeable influence can be seen on American and British fiction in the 20th century and he continues to inspire budding authors till date.

MAIN Sources:-

Reynolds, Michael. 2000. “Literary Masters Vol 2: Ernest Hemingway”. P65-72. The Gale Group.

Ernest Hemingway (1990). “The Art of the Short Story”. In Benson, Jackson (ed.). New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Duke University Press.

Baker, Carlos. 1952. “Hemingway – The Writer As Artist”. Xiiv, P28,49,117 Princeton University Press 1963.

Putnam, Thomas. 2006. “Hemingway on War and Its Aftermath”. National Archives

Rideout. Walter B. 2007. “Info – Sherwood Anderson A Writer in America, Volume 2”. The University of Wisconsin Press.

“The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954”. Nobelprize.org

“Star style and rules for writing”. KansasCity.com