The Russian Empire had faced several reverses in the years leading to World War I including defeat at the hands of a much smaller Japan and the 1905 Revolution. In 1907, Russia strengthened ties with France and Britain forming the Triple Entente, which was the major Allied force in WW1 against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria. As war began in August 1914, Russian troops were quick to cross the German border and a few days later they invaded Austrian Galicia. Things went downhill thereon as the Austrians held off the advance and the Germans inflicted devastating defeats on the Russians at Tannenberg and Masurian Lake. As Russia’s position further weakened in 1915, Tsar Nicholas II took over as military Supreme Commander. This, however, further deteriorated his image as every defeat was now closely tied to him. The February Revolution in 1917 led to tens of thousands taking to the streets in protest, forcing the Tsar to abdicate. The Bolshevik Revolution then overthrew the Provisional Government and, on March 3, 1918, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, bringing an end to Russia’s participation in the Great War. Here is a detailed analysis of Russia’s participation in World War I including all the major events in which it was involved.

Looking For Change

At the turn of the 20th century, Tsar Nicholas II ruled the Russian Empire as an absolute monarch. Imperial Russia was among the largest empires in the world, existing across Eurasia and North America since 1721. However in the decades leading up to World War I, Russia was a pale shadow of its former self, despite its still formidable reputation. Loss to a much smaller Japan in the Russo Japanese War of 1904-05 was an indicator. It was followed by the 1905 Revolution which forced the Tsar to concede civil rights and a parliament to the Russian people, shaking the foundations of the empire. The State Duma (Parliament) thus formed was only a consultative body and many Russians felt that this was not enough, remaining dissatisfied.

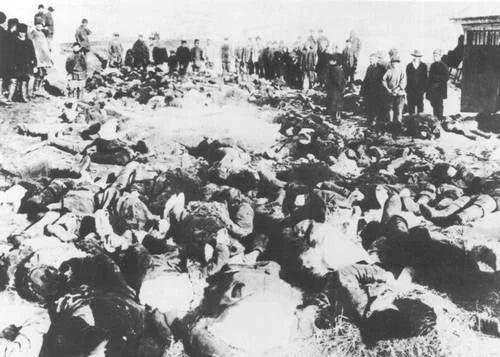

Industrial strikes in Russia were common in the era, which in 1912, saw the massacre of hundreds of striking miners in the Lena gold fields. Adding to that, the rise of nationalism among ethnic minorities of Europe had not left the Empire untouched. The majority of its estimated 166 million population were Slavs but there were dozens of other nationalities which increasingly wanted regional autonomy and were a constant source of political conflict. Muddled with internal strife, dissatisfied populace, disruptions and strikes; the Empire in 1914 was not ready for a major conflict and was on a cusp of change.

Entry Into WW1

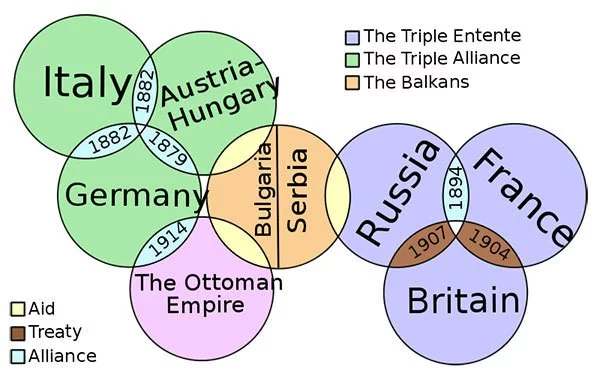

The Russian government considered a rising and ambitious Germany to be the main threat to its territory. The threat was reinforced with Germany joining hands with another neighbor Austria-Hungary in a military alliance. In 1907, Russia strengthened ties with France and Britain, further polarizing the political scenario in Europe with the formation of the Triple Entente.

As the Balkan problem exploded politically in June 1914 with the assassination of Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand by a Bosnian Serb, Russia was morally bound and politically motivated to come in support of the pro-Slav Serbian nation. The primary concern among the top leaders was maintaining Russia’s status as a Great Power. They didn’t want Russia to become another second tier empire ripe for dismemberment by the other Great Powers.

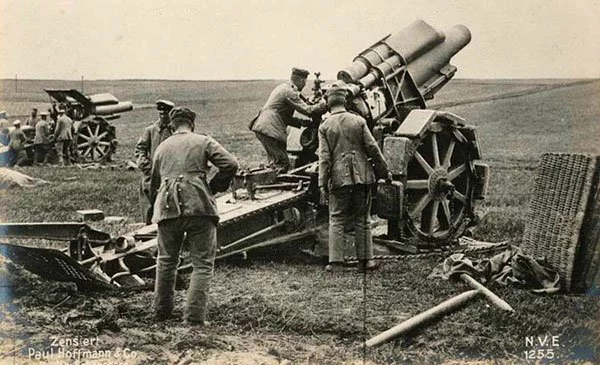

Russia was quick to mobilize once Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, which immediately led to Germany declaring war on Russia, and the war escalated within days to engulf all the Major Powers, their colonies and many other independent nations. In 1914, the Russian Army had the largest standing army in the world with close to 1.5 million men. There were however issues with lack of modern weapons; and poor road and railway infrastructure that reduced the effectiveness of the force.

The entry of Russia into the First World War provoked a powerful upsurge of patriotic sentiments which encompassed all social classes and regions of the country. This was mostly common among all European nations and was later used metaphorically as “the 1914 mood” in Western historiography. More importantly for Russia though, it acted as a glue among the populace and 96 percent of those subject to conscription appeared at the mobilization commissions, growing the strength of the forces to 6.5 million by the end of 1914. Almost all parties agreed to fight the war hand in hand with the monarch in a “sacred union”, and the parliament went into recess to let the military and government take charge during the war.

Initial Military Campaigns of 1914-15

Russia had promised its French allies of a military campaign against Germany shortly after the declaration of war. They did not disappoint and on 11th August, 1914 Russian troops crossed the German border. A few days later, they invaded Austrian Galicia. Things went downhill thereon as the Austrians held off the advance and the Germans inflicted devastating defeats on the Russians at Tannenberg and Masurian Lake.

However, this failed Russian advance into East Prussia did disrupt Germany’s Schlieffen Plan, which aimed at ending the French threat in a quick decisive conflict so that forces could be transferred quickly to combat the much larger Russian army. Hence, the Russian invasion probably prevented the fall of Paris. However, it also signaled the beginning of an unrelenting Russian retreat on the northern sector of the Eastern Front. There was better news to the south, with the taking the key Galician city of L’viv on 3 September and the Austro-Hungarians being forced to retreat. By November 1914, the Russians were at the gates of the ancient Polish capital of Kraków and were scaling the Carpathian Mountains to the south. On the third front in the Middle East, the Russians prevailed again against the Ottoman invasion at Sarikamish.

1915 was a disastrous year for the Russian Empire, where their grand plans for invading Hungary were spoiled by a combined Central Powers offensive at Gorlice Tarnów. Beginning on 2nd May 1915, the Russian faced a series of defeats forcing retreat from territories occupied in 1914. In the north, German pressure cracked Russian defenses and, by September 1915, all of Russian Poland and Lithuania, and most of Latvia, were overrun by the German army. Russia however could still not be knocked out of the war.

The Tsar Takes Command

The initial patriotic fervor in Russia faded as the military losses began putting strain on the Empire. The sacred union collapsed, government was heavily criticized, industrial strikes returned and ethnic riots broke out in major cities especially against the Germans. This summer crisis of 1915 saw the Empire in disarray with thousands injured, distraught and retreating soldiers; and outbreak of epidemic diseases. Conscription was widened and the economy continued to decline.

The demands of Polish autonomy garnered a lot of support but Tsar Nicholas II had other ideas. Several ministers were sacked and the Duma was disbanded to institute a more autocratic rule. Moreover, the Tsar took on the position of military Supreme Commander and left for the front in September 1915.

Towards The End Of Monarchy

Nicholas II’s decision to personally take command of the army further weakened his control over the nation. Now every defeat was being closely tied with him, shattering the image of a divine infallible Tsar. The Tsarina now played a more active role in internal affairs and bureaucratic anarchy grew in the absence of strong leadership from above. Her close association with her council, mystic and healer Rasputin, led to wild rumors of them being discussed in the populace, including talk of them being German spies. The impulsive decisions and the erratic behavior during her rule brought further disrepute to the Royal family.

The Russian Forces fared better in 1916. The Brusilov Offensive of June brought significant victories over the Austrians – capturing Galicia and the Bukovina. Moreover, the Russians were also more than holding her own in Transcaucasia, against Turkey. But the internal politics and social order had deteriorated beyond repair towards the end of 1916 and revolutionary voices were rising within the country. By mid-November, the Tsar had lost the support of even the ultra-conservative monarchists. A few months later, in March 1917, Tsar Nicholas II was forced to abdicate, ending more than three hundred years of Romanov rule in Russia.

The February Revolution

Behind the lines, the urban women in Europe had borne the brunt of war. With most young men on the front, they were suddenly pushed into industry and the paid sector, many times at low wages, while also taking care of domestic work. Moreover, shortages of food and supplies deteriorated living conditions in Russia and the war seemed to have no end, further angering the masses.

On 8th March 1917 (23 February 1917 Russian calendar), Russian women took to the streets in Petrograd on International Women’s Day protesting and calling others to join them. As the crowds gathered and the soldiers were asked to use force, they mutinied and joined the movement. The February Revolution in Russia led to political and economic gatherings; and tens of thousands took to the streets in protest forcing the Tsar to abdicate. The newly formed Provincial Government of the new republic decided to continue to fight the war alongside the rest of the Entente.

The Bolshevik Revolution

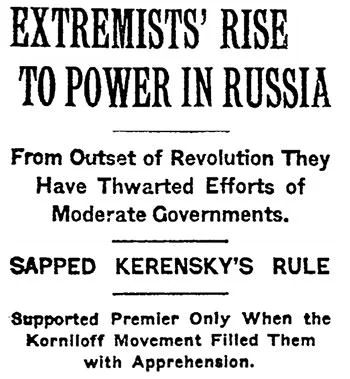

The end of Tsar’s rule and establishment of the Provisional Government could only briefly douse the anger in the Russian population. As Russia continued in the war, economic, social and military pressures kept on mounting. The leaders faced the wrath of the public and there were further mass strikes and peasant uprisings in different parts of the country.

Vladimir Lenin’s party, the Bolsheviks, saw a tremendous revival of their fortunes in 1917. They had opposed the war since the beginning, had denounced European empires since long and had pioneered the slogan of “national self-determination”. This helped them make a convincing case of pulling Russia out of the war in case of assuming power. This, in turn, won them a lot of support among the people. Vladimir Lenin, who had been living in exile in Switzerland since February 1916, organized his return negotiating with the Germans. Recognizing that Lenin and his dissident group could cause problems for their Russian enemies, the German government agreed to permit 32 Russian citizens to travel in a “sealed” train carriage through their territory.

On 25 October (7 November Gregorian calendar), the Bolsheviks launched a successful and almost bloodless coup that overthrew the Provisional Government. Soon after, it was announced that all power would henceforth reside in the hands of the worker’s councils (soviets), laying the first foundation stone for what would later evolve into the Soviet Union.

Exit From War

Lenin had gained power on the promise of pulling Russia out of the War. The Russian Army was in distress but the Germans also wanted to concentrate more on the Western Front. A ceasefire was thus soon established after the October Revolution and peace negotiations began in Brest-Litovsk in the following weeks.

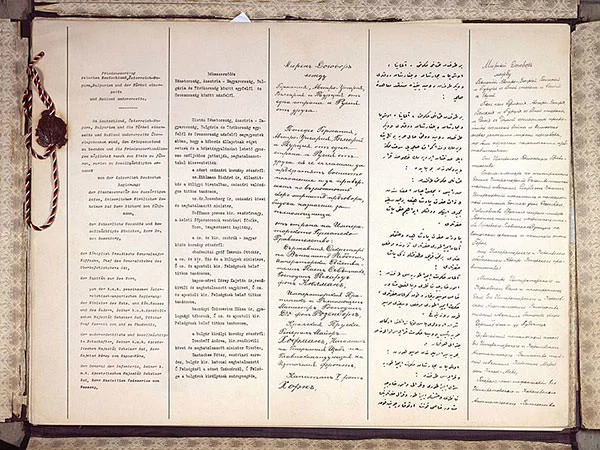

The Russian situation was bleak and the Central Powers imposed strong punitive actions including cession of all of the Old Russian western borderlands. The Bolsheviks refused the punitive peace at first but the Germans called their bluff, taking military action and threatening Petrograd. The Soviet delegation thus signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on punitive terms on March 3, 1918, bringing an end to Russia’s participation in the Great War.