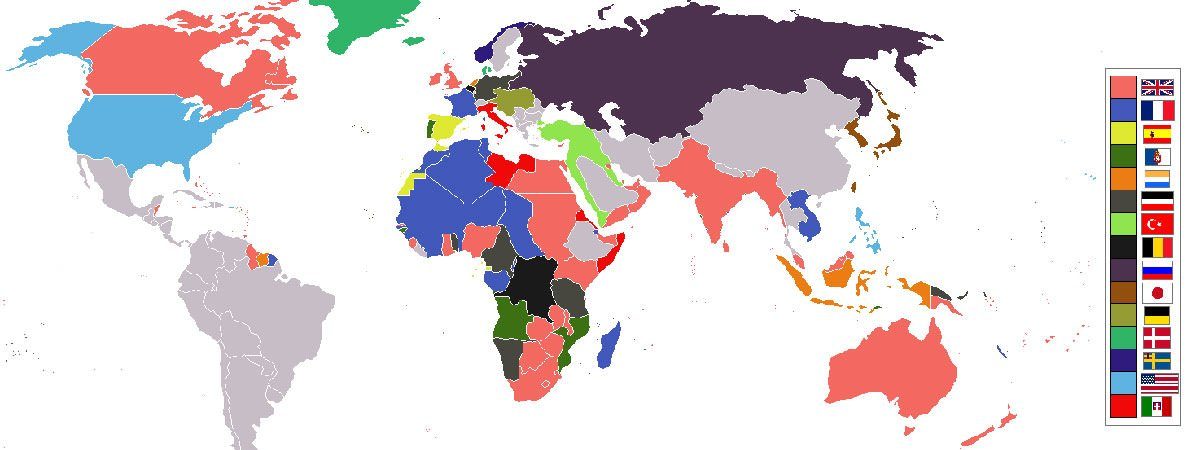

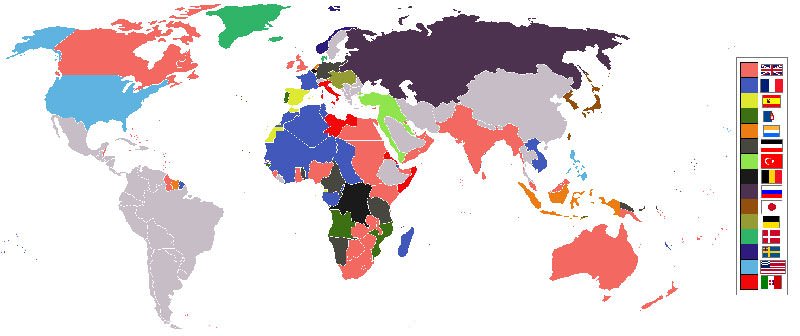

The Major Powers of Europe involved in the First World War were Great Britain, Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary and France. By the end of the 19th century, these nations had been long expanding and managing their imperial rule over their colonies. Imperialism is a system where a nation or state (imperial power) establishes control over another nation or state or land (colony) and uses its people and resources to enrich and empower itself. The colonies were conquered through coercion, annexation, political subterfuge or by military force. They were sometimes ruled through puppet rulers but the imperial power often had a military presence in its colony; to suppress any uprisings and to deter rival imperial powers. The latter part of the 1800s was a period of turmoil in Europe. The rising nationalism and the dwindling Ottoman Empire created political instability and opportunity in eastern Europe. Moreover, the competition among the Great Powers meant an atmosphere of distrust and need for protecting colonial territory while looking for newer colonies in Africa. Here is detailed analysis of the clash of imperialistic ambitions of the major powers which in turn led to World War I.

Germany And Great Britain

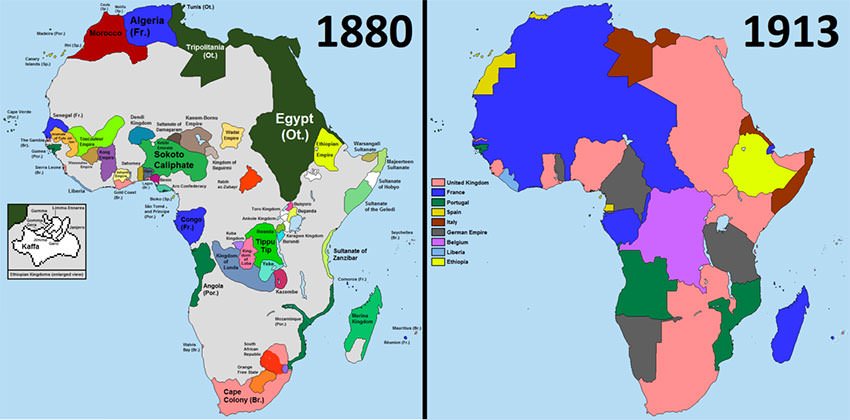

The pre-World War I era was dominated by Great Britain with the help from its vast colonies in India, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, Egypt and a host of other areas like the Caribbean islands. Germany had entered the colonial race much later only to find that all the best territories and strategic ocean highways were already dominated by Britain, France and others. Germany slowly began expanding its influence seizing control of modern-day Tanzania, Namibia and Cameroon in Africa; German New Guinea; some Pacific islands; and gaining a foothold in the province of Shandong in China. In the period of New Imperialism (1881 and 1914) of European colonization of Africa, Germany was a major roadblock for Britain’s elaborate plans. The British dreamed to build a transcontinental railroad from Cairo in Egypt to its Cape Colony (South Africa) on the southern tip of Africa, and Germany’s African colonies were a problem for them.

Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty

This Anglo-German treaty of 1890 was among the rare examples of British and German being on the same page in the pre-WWI era. British gave up the island of Heligoland, which was of high strategic interests to the Germans; giving them a free hand to control and acquire the coast of Dar e Salaam that would form the core of German East Africa (later Tanganyika). In return Germany gave up Wituland and some parts of East Africa which were important for the British to build a railway to Lake Victoria. Germany also promised not to interfere with British actions in Zanzibar, which resulted in Britain gaining control of the region after the Anglo-Zanzibar War of 1896. This treaty caused a public protest in Germany where it was felt that Germans had swapped an African empire for a tiny Heligoland. It also led to the formation of the Pan German League, a powerful nationalist group that would influence German politics in the future.

Kruger Telegram

The Kruger telegram was sent by German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II to president of the Transvaal Republic Stephanus Kruger in 1896. It was a message congratulating the president for his success in repelling a British raid. The telegram is considered a diplomatic mistake as the German emperor surrendered his neutrality and symbolically joined the Boers against British South Africa, when it was not necessary. The telegram was later picked by the British press to build sentiment against Germany.

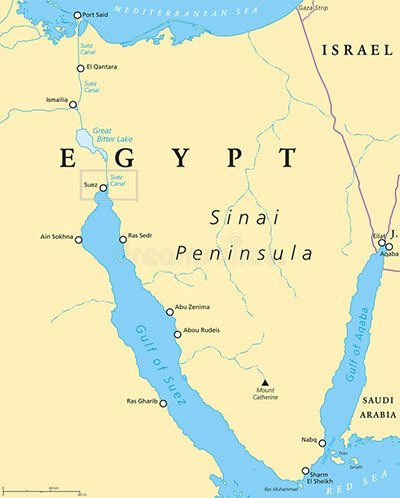

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal in Egypt had begun operating in 1869. A decade later, in 1879, Britain and France had seized joint financial control over the country. The canal connected the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and was vital to British colonial interests. Britain was thus under intense political pressure, to secure this key waterway between the East and the West. Losing the Suez Canal meant a threat to its imperial interests in India and China. In 1882, seeing the rising interest of Germany in Africa, the French penetration eastward across central Africa towards Ethiopia and the Portuguese control on the coasts, Britain was nervous about its vital trade route through Egypt and its Indian Empire.

German Weltpolitik

For almost a decade after its unification in the 1871, Germany had shown little interest in acquiring colonies. This changed in the 1880s with mad rush to Africa. In 1884, Germany acquired Togoland, the Cameroons and South West Africa (now Namibia). Thus, in a few years, it became the third largest colonial power in Africa, acquiring an overall empire of 2.6 million square kilometers. The ambition of the new German Empire was growing and, under the new Emperor Wilhelm II, Germany adopted the imperialistic foreign policy of Weltpolitik in 1890. The Weltpolitik changed the focus of Germany from threat of a two front war and maintaining its newfound status, to more aggressive imperial ambitions. The policy would lead to the Tirpitz Plan and the Fleet Acts of 1898, and was among the primary reasons for the naval arms race between Britain and Germany in the early 20th century.

“We wish to throw no one into the shade, but we demand our own place in the sun.”

German Foreign Secretary Bernhard von Bülow, 1897

Germany And France

The Franco German War of 1870–1871 had resulted in a French defeat and Germany annexing French territory in Alsace and Lorraine. The French and German rivalry would continue to be relevant to European politics leading up to the First World War with both sides working against each other. The two powers came to loggerheads twice, pursuing their colonial ambitions in Morocco. In 1905, German Emperor Wilhelm II visited the Moroccan capital of Tangiers and made a speech in favor of independence of the nation. This was against French influence in the region. The crisis escalated with both sides posturing aggressively, Germany mobilized reserve army units in late December and France actually moved troops to the border in January 1906. The Algeciras Conference finally calmed this First Moroccan Crisis whereby France yielded certain domestic changes in Morocco but retained control of key areas.

A Second Moroccan Crisis would emerge five years later. In 1911, a rebellion broke out against the pro French ruler of Morocco, Sultan AbdelHafid. To assert its authority, France deployed 20,000 troops in April 1911 in guise of protecting European lives in Morocco. This was too much for Germany, and a gunboat “SMS Panther” was sent to the Moroccan port of Agadir. This was later replaced by a bigger “SMS Berlin”. The crisis resolved in November through diplomacy, with France taking Morocco and conceding some parts of Congo to Germany. British backing of France during the crisis reinforced the Entente between the two countries, while increasing Anglo-German estrangement.

Austria-Hungary and Russia

As the Ottoman Empire weakened at the end of the 19th century, the major powers were keenly developing their strategies regarding the Balkan Region. Russia developed a strategic depth in the region supporting a pan-Slavist policy, which aimed at uniting all Slavonic-speaking peoples under the Tsar’s leadership. This was against the interests of many powers especially Austria-Hungary which backed an anti-Slavic policy both domestically and abroad leading to resentment among its own Slavic subjects. Efforts were made to reach a common ground in the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, but the 1908 Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia fractured the relations further. The rivalry would finally lead to the assassination of Austrian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914 and this in turn would flare up the First World War.