Prehistoric art is a term used to refer to art made in the distant past, roughly corresponding with the stone age which lasted from 3.3 million years ago to around 2,000 BCE. It is divided into two main categories: rock art, or the art created on rock surface; and portable art, which includes sculptures, beads, pendants, manuports etc. Manuport is an unmodified object transported from its original environment and relocated, due to its aesthetic character. They are considered the earliest examples of art. Here is an overview of prehistoric art including its discovery, characteristics, purpose and more.

Table Of Contents

VIDEO

S1 – Prehistoric Era

Prehistory is the period of human history before the invention writing and keeping of written records. This is a very long period, ten million years according to current theories. The first known use of stone tools by hominins (modern humans, extinct human species and all our immediate ancestors) is dated to around 3.3 million years ago. The first full writing systems appeared in several regions independently. The first among them was in Mesopotamia around 3,400 BCE.

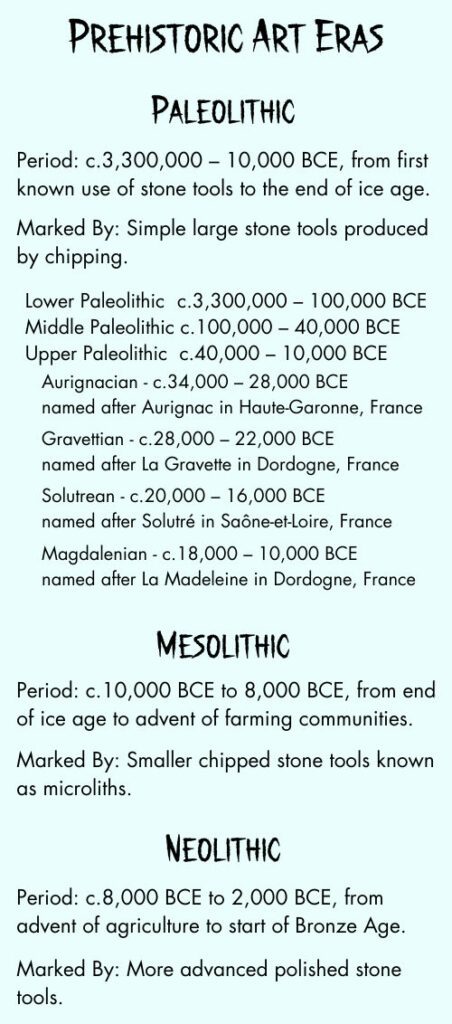

Prehistorians have used the activity of tool-making as the defining feature for measuring time. The Stone Age, which lasted from around 3.3 million years ago to around 2,000 BCE, is generally taken as the time period for Prehistoric art. It is divided into three eras: the Paleolithic, the Mesolithic and the Neolithic; in other words the Old Stone Age, the Middle Stone Age and the New Stone Age. These periods are marked by change in technology of making stone tools.

S2 – Prehistoric Art Definition

Technically, prehistoric art is art made by people in those societies where a writing system has not been developed. There have been societies in recent times which have had no writing system. However, we don’t call their art prehistoric as it is recent. We generally use the term ‘ethnographic arts’ for arts developed by such societies. Moreover, the implication that societies with oral traditions are less cultured than those with writing is not true.

‘Archaeological art’, or art of past cultures which we study using archaeological methods, may be a more appropriate term. Nonetheless, we will use the term ‘prehistoric art’ as it is widespread and most people relate to it. Moreover, we will limit the term to art made in the stone age as this is in keeping with the classification of prehistoric art in many texts.

S3 – Prehistoric Art Types

Prehistoric art encompasses all art-like manifestations of the distant past. It is divided into two main categories:-

- Rock Art, which consists of markings on rock surfaces the were intentionally produced by members of the genus Homo (human beings or species closely related to humans like Neanderthals).

- Portable Art, which is made up of a diversity of materials, whose key determining feature is that they are small enough to be carried easily by humans, and which in many cases can be worn on the human body.

Rock art can be divided into two principal classes on the basis of the method used to manufacture it: petroglyphs, which are produced by a reductive process; and pictograms, which are produced by an additive process. Petroglyphs are found in two forms: sgraffiti, defined by color contrast; and relief petroglyphs, defined by relief depth. Both of these types may be made by percussion or abrasion. Pictograms include stencils, paintings, drawings, beeswax figures etc. It is important to note that some rock art has been created using both reductive and additive processes.

Portable prehistoric art includes decorative items like beads and pendants; devices used for retention and retrieval of information, like message sticks; portable engravings and figurines; plaques; objects bearing series of notches and lines; ceremonial objects; and manuports.

S4 – Prehistoric Art Discovery

Rock Art

Apart naturally preserved sites, Prehistoric Rock Art was always known to the locals though they didn’t know its age. The first known mention of rock art in a written text is by Chinese philosopher Han Fei in his book Han Fei Zi. It was written in 3rd century BCE about 2,300 years ago. Numerous other references to rock art may be found in literature from around the world. By mid-19th century CE, as archaeology became established, the great antiquity of humankind and prehistory became accepted. Consequently, the study of prehistoric art became widespread, systematic and better documented.

In the 1860s, Archibald Carlyle, an English archaeologist active in India, discovered rock paintings in shelters at Morhana Pahar, near the village of Hanmana in Bhainsaur, Uttar Pradesh. While numerous other discoveries of prehistoric sites had been made before this, Carlyle was remarkable because he was the first to recognize that some of the paintings discovered must be prehistoric.

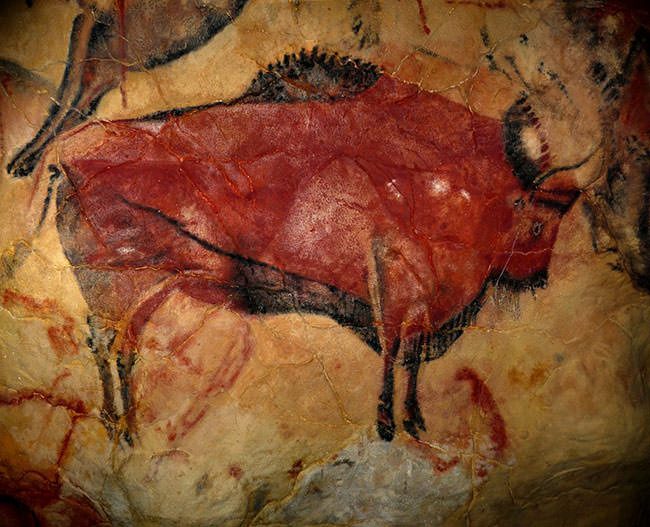

Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola was a Spanish jurist and amateur archaeologist. In 1878, he discovered Paleolithic paintings on a cave on his property, known as the Altamira cave. Due to the sophistication of the art found, experts considered Sautuola’s discovery a hoax. He died in 1888, still not credited for his monumental find.

At the end of the 19th century, there were a number of discoveries of painted/engraved caves in France. These include La Mouthe (1895), Pair-non-Pair (1896), Les Combarelles (1901) and Font-de-Gaume (1901). As images of long extinct animals were discovered from these sites, doubts over their authenticity as prehistoric art began to mitigate. In 1902, prehistorians of the time declared Altamira to be authentic.

Sculpture

The first Paleolithic female sculpture was discovered at Laugerie-Basse, located in Dordogne, France. It was found in 1864 by Paul Hurault, 8th Marquis de Vibraye, an amateur archaeologist from France. He named it Venus Impudique (“Immodest Venus”) because, unlike in classical depictions of Venus, the depicted female made no attempts to hide her sexuality.

The term “Venus” was then used 30 years later by French archaeologist Édouard Piette in a satirical manner, just like it was used for Venus of Hottentot. Piette used it to describe only what he considered grotesquely obese figures. Since then the term “Venus” was applied to each new find of a Paleolithic female sculpture. Thus the term is not related to fertility or to comparability with classical art. It is a misnomer which reflects European racist attitude at the time.

S5 – Prehistoric Art Characteristics

Geometric arrangements of lines, notches and dots are frequently found in Prehistoric art. Historically these signs were given literal interpretation like spears, traps, nets etc. However, now many of these signs are viewed as symbolic complements to the animal/human imagery. In some cases geometric signs might be pictorial representations of objects. Like the zig-zag shapes at Fornols probably represent lightening, which is frequent in the area. However, in most cases such correspondence is not evident.

Paleolithic Cave Art

- Animals dominate Paleolithic cave paintings.

- Usually, individual images have their distinct space and don’t overlap.

- Natural forms of the caves are exploited to give volume to depicted animals.

- Acoustic qualities of the caves may have played a part in choosing the location for cave art.

Paleolithic Sculpture

- Human representations are few in comparison to animals.

- Pregnant females dominate human depiction with males being a rarity.

- In some cases, the reliefs provide views of characteristic animal behaviors like mating.

Mesolithic Art

- Like the Paleolithic era, rock paintings dominate the surviving examples of Mesolithic art.

- Due to warmer climates, art moved from caves to vertical cliffs or walls of natural rock.

- Humans, not animals, dominate Mesolithic rock art.

- The depicted humans may be seen hunting, dancing, running, playing games, etc.

Neolithic Art

- Sculpture made a comeback in Neolithic era after being nearly absent in the Mesolithic.

- It was no longer restricted to carving and was now also fashioned out of clay and baked.

- Like the Mesolithic, Neolithic painting depicts more humans than animals.

- These humans became more identifiable unlike their Mesolithic predecessors.

S6 – Prehistoric Art Techniques

Petroglyphs

Petroglyphs, as mentioned earlier, are rock artworks which are produced by a reductive process. Direct percussion or pounding accounts for most, if not all, percussion petroglyphs. The other type of petroglyphs are made by abrasion. Mur-e is an aboriginal word from the Brooandik language for a tool used for making a petroglyph. Several striking characteristics of mur-e are as follows:-

- They are usually under 150gm and rarely over 250gm. This corresponds to a maximum dimension of 6 to 8cm.

- There is a preference for pieces with a thick end to be held in hand and a pointed end to strike the rock surface. Flat and elongated shapes are also seen. Round pebbles are also used for patina (outer surface of rocks) bruising.

- There is a preference for dense quartzites and crystalline quartz of various types as the material, when available.

- Several types of other materials have been used to produce petroglyphs especially where the rock surface is soft.

- The softest rock used is carbonate speleothem, or moonmilk. It can be marked by the slightest finger touch.

Pictograms

There is a lot of ethnographic information available about the technology of pictograms, mostly from Australia. The various colors are obtained as follows:-

- Red ochre was a widely traded commodity. Substitutes were also used, including yellow or brown limonite, that were roasted to obtain a red color.

- White was frequently obtained from kaolin, huntite, enstatite, carbonate, gypsum or selenite; even from finely grounded minerals like quartz, microline, muscovite and jarosite.

- Black pigments are mostly of charcoal or manganese oxide.

- Yellow and various hues of brown were obtained from iron minerals, clay, from the dust inside termite nests, siderite, and locally from a fungus.

- Glouconite provided the rare bluish colors.

Hard pigments were pounded, ground or eroded into a powder. Ground patches of rock have been found at thousands of rock art sites. Various liquids provided the solvent, suspender or binder required in paint production. These include water, urine, blood, semen, honey, egg-white or fat of various animals. Plants were used to extract numerous other binders.

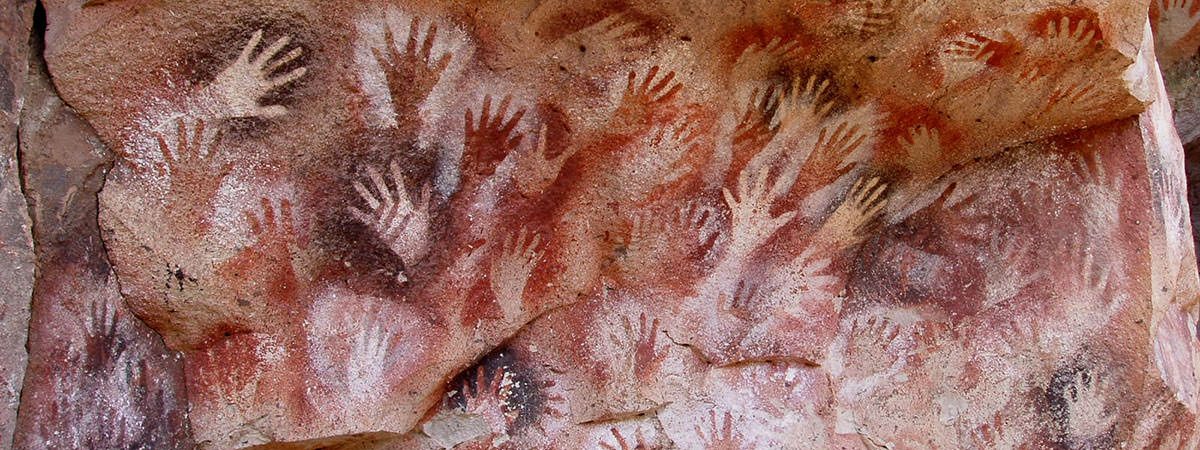

There is a lot of literature on the Australian use of paintbrushes and the application of paint on rock surfaces. In Arnhem Land, brushes were recently made from tree barks, pandanus leaves, kapok bush, palm leaf fibers or twigs whose ends were chewed. Paints were frequently applied with fingers or whole hands in Australia and elsewhere. Prepared paint was contained in the mouth of the artist or a suitable container, like a seashell or a piece of bark.

Apart from stencils, linear pictograph motifs were also produced by spraying paint directly from the mouth into a narrow gap made by the hand. This is a more effective form of paint application than brushes. This is because sprayed paint tends to have better penetration and adherence, especially on rough and porous surfaces.

Rock drawings were made with hand held pieces of pigment applied dry to the rock surface, like a crayon. This was a widespread technique but its results were less permanent. Drawings can often be distinguished from paintings, especially microscopically. The crayons used for drawings are sometimes found on sites, even in sediment layers.

Sculpture

Sculpting and finishing of prehistoric miniature sculptures would have been a difficult task considering the technology available. Splitting and wedging was followed by scraping, gouging, incising, grinding and polishing. Powered hematite was used as the abrasive for polishing. Among the best known Paleolithic sculptures is Venus of Brassempouy. It is one of the earliest detailed representations of a human face. The well preserved surface of the statue shows remarkably clear traces of several different techniques: cutting, incising, grinding, polishing, scraping, gouging and chiseling. Many of these techniques have been produced by the same tool, a stone burin.

S7 – Prehistoric Art Purpose

With some rare exceptions, there is nothing to tell us reliably what a rock art motif depicts or means. Most rock art interpretations are based on the perception of observers. There is no rational explanation for the traditional assumption that ‘researchers’ have some additional insight into the meaning of rock art acquired by many years of ‘observing’ such art traditions. Thus most theories about the meaning of prehistoric art has no value in scientific study of the subject. Nonetheless, we will cover the most prominent theories about the purpose of prehistoric art.

Art For Art’s Sake

The simplest view among scholars about the purpose of prehistoric art was that it was merely decorative, i.e. it was “art for art’s sake”. This view persisted at least into the 1920s. While most of the cave paintings and engravings are readily accessible, there are some which have been created in places that are difficult to access. The “art for art s sake” explanation is highly unlikely for these sort of works. Moreover, as ethnographic research provided information about the active hunter-gatherer societies around the world, it became clear that art was anything but for its own sake in these societies.

Hunting-Fertility Magic Theory

In the 20th century, it was proposed that prehistoric artworks were magical acts to ensure the success of a hunt or to increase reproduction and fertility. The hunting-fertility magic theory believes that prehistoric humans perceived an image as equal to the animal it depicted. By possessing the image, they thought that they had some control over the animal thus increasing the chance of a successful hunt. This was corroborated by the fact that some animals were depicted with spears cast on them. The reason behind sculptures and paintings of pregnant women and animals was explained as a magical act to control reproduction and fertility.

The hunting-fertility magic theory dominated the scene until 1950s. However, as more prehistoric art was discovered, a flaw in this theory became apparent. The study of food deposits at some sites clearly implied that the artists were not portraying the animals they ate. For example, at Lascaux, 90% of the food remains were that of reindeer but the animal was represented only once. Similarly, at Grotte Chauvet, 72% of the animals depicted were not hunted.

Shamanistic Interpretation

In 19th and 20th century, anthropologists studied the rock art of Southern Africa and found it to be related to shamanistic practices of local bushmen. Scholars drew parallels between this and prehistoric cave art to link shamanism with it. The theory proposed was that cave art was a pursuit to contact a parallel spiritual universe.

In the shamanistic interpretation, geometric signs are seen as representation of hallucinations in a trance state. Moreover, where natural contours are exploited to create an artwork, the shaman is using his power to bring the spirit of the animal to the surface. The spotted horses at Pech-Merle, where the right side of the rock is shaped like a horse’s head, is one example of this. Paintings made in remote areas are seen as exploration of deep underground for spiritual visions.

Dialogue Between The Artist And The Cave

Some scholars believe that the paintings played a role in early religion as images of worship. Recent researchers have also focused on the individuality of each cave describing the process of creating art in them as dialogue between the artist and the cave. They study the choice of subject, color and technique in respect to surface, texture, light conditions, preexisting forms and even acoustic qualities of the cave.

A Combination of Various Theories

There is a tendency of scholars to apply a one-for-all interpretation for Prehistoric art, whether it is “art for art s sake”, “hunting-fertility magic” or “shamanism”. The proponents of these theories present selected images to justify their interpretation, leaving the other majority unexplained. What emerges today is a picture of enormous complexity. Recent scholars thus believe that one explanation is not sufficient for all prehistoric artworks.

Sources:-

S1:-

Buis, Alena. “Art and Visual Culture: Prehistory to Renaissance”. “Prehistoric Art”.

Clayton, Ewan. “Where did writing begin?”. British Library Board.

Janson, H. W., Davies, Penelope J. E. “Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition”. p. 9.

S2:-

Conkey, M.W. (2001). “Prehistoric Art”. “International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences”.

S3:-

Bednarik, Robert G. “Rock Art Science – The Scientific Study of Paleoart”. pp. 1, 5, 177.

S4:-

Bahn, Paul G. (1997). “The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art”. pp. 1, 49, 67.

White, Randall. (2003). “Prehistoric art: the symbolic journey of humankind.” pp. 45, 54, 55.

S5:-

White, Randall. (2003). “Prehistoric art: the symbolic journey of humankind.” pp. 71-120.

Esaak, Shelley. (Sep 01, 2018). “Art of the Mesolithic Age”. ThoughtCo. Dotdash Meredith.

Unit 3 “Mesolithic Art”. eGyanKosh.

Esaak, Shelley. (Aug 26, 2018). “Neolithic Art”. ThoughtCo. Dotdash Meredith.

S6:-

Bednarik, Robert G. “Rock Art Science – The Scientific Study of Paleoart”. pp. 37-48.

White, Randall. (2003). “Prehistoric art: the symbolic journey of humankind.” pp. 71, 87.

S7:-

Bednarik, Robert G. “Rock Art Science – The Scientific Study of Paleoart”. p. 153.

Janson, H. W., Davies, Penelope J. E. “Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition”. pp. 5, 6.

White, Randall. (2003). “Prehistoric art: the symbolic journey of humankind.” pp. 50-58.

“Art That Changed the World”. DK. Penguin Random House. p. 13.