In the decades preceding World War I, Germany rose rapidly as a nation becoming the largest economy in Europe and a major military power. After the assassination of Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand by a Bosnian Serb in June 1914, Germany pledged unconditional support to its ally Austria-Hungary, a major reason for the conflict turning into a world-wide war. As war began, Germany wanted to eliminate the French threat in a quick decisive conflict on the Western Front so that it could then concentrate on the Eastern Front to combat a much larger Russian army. Though it had initial success, the plan failed and war on the Western Front turned into a deadlock. Meanwhile the Central Powers led by Germany tasted success against Russia, ultimately forcing the Russians to withdraw from WW1 by the end of 1917. A war-weary nation by then, Germany tried to end the war through the Spring Offensive in early 1918. Though it was initially successful, the offensive failed and the counter Allied offensive ended the war in their favor. Here is a detailed analysis of Germany’s participation in World War I including all the major events in which it was involved.

A Rising Power

Early 19th century had seen a rise in nationalism in Europe and movements regarding the unification of Germany had spawned over the years, but nothing substantiated. It was not until 1862, when Prussian King William I appointed Otto von Bismarck as the new President, that things began to take shape. Bismarck successfully concluded war on Denmark in 1864, with Austria in 1966 and with France in 1870. These events marked the emergence of a new Empire and led to the unification of Germany in 1871, with Prussia being the largest state.

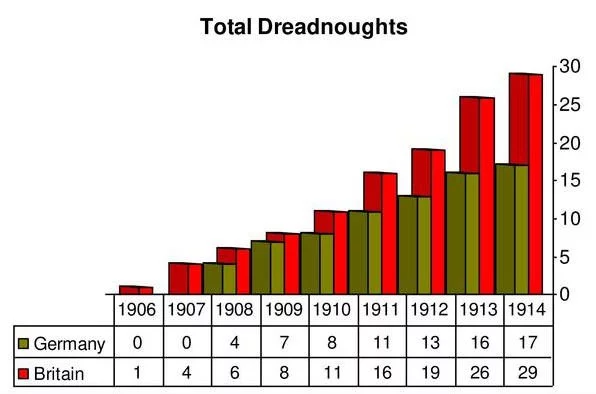

Now as Chancellor of Germany under Emperor William I, Bismarck secured Germany’s position as a great nation by increasing industrial output, forging alliances, isolating France by diplomatic means and avoiding war. In 1890, however Bismarck was removed by the new emperor Wilhelm II, who wanted Germany’s “place in the sun” and had colonial ambitions to challenge Great Britain and France. The German naval program was introduced in 1898 in a bid to challenge Britain as the foremost world power. This, in turn, led to a naval arms race between the two countries. By the turn of the 20th century, Germany was also recognized as having the most efficient army in the world. This military expansion and modernization was heartily endorsed by the newly crowned Kaiser Wilhelm II and was a cause of concern and threat for the foremost imperial powers of the time.

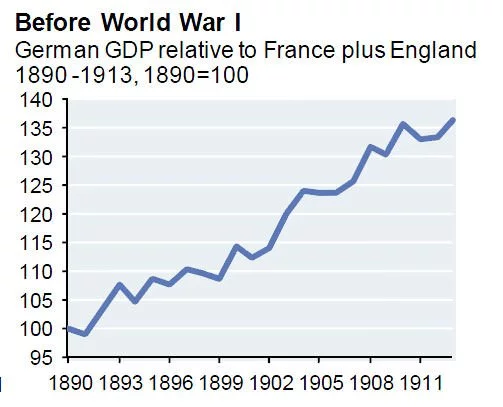

The German growth story preceding the Great War was the fastest in the world, with its production and exports quickly catching up with the British and the French. Between 1870 and 1910 the population of Germany had increased from 24 million to 65 million. Over 40 per cent of this fast-growing workforce was employed in industry. Germany was investing in and benefiting from modern industries like electrical and chemical, while it also became a leader in textiles. Between 1880 and 1913, coal production increased by 400 percent. Other industries such as steel, engineering and armaments had also grown rapidly. In a thirty year period Germany’s international trade had quadrupled making it the largest economy in Europe.

July Crisis and Entry Into War

On 28th June 1914, Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by Serbian revolutionaries which had ties with the Serbian military. This was a grave situation as the Great Powers in Europe were politically divided and to a large extent committed into two factions: the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria Hungary and Italy; and the Entente of France, Russia and Britain.

In the diplomatic dealing that ensued known as the July Crisis, Germany was approached by their ally Austria Hungary. The German government assured Vienna of its unconditional support for action designed to overthrow Serbia, and encouraged quick action. For the German military elite this was an opportunity to test the Entente and, though they preferred a localized conflict, they were confident of Central Powers emerging victorious in case of a European war. The German government however was frustrated by the lack of determination and delay by the Austro-Hungarians and many among them neither expected nor welcomed an all-out European War. On July 28, Austria-Hungary opened hostilities against Serbia and soon Russia mobilized against Austria-Hungary. Germany followed this by sending an ultimatum asking Russia to demobilize. It was ignored and on 31st July 1914, Germany declared war on Russia.

Schlieffen Plan

The German army opened the war on the Western Front with a modified version of the Schlieffen Plan, designed to quickly attack France through neutral Belgium before turning southwards to encircle the French army on the German border. The Schlieffen plan aimed at ending the French threat in a quick decisive conflict by deploying majority of the forces on the Western Front. These forces could then be transferred quickly to the Eastern Front to combat a much larger Russian army.

Things went to plan initially with the conquest of Belgium, Luxemburg and impressive advance into French territory in the first few weeks. However the French, with the help of the British, were able to hold the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September). The Schlieffen Plan had failed and the ensuing stabilization of the Western Front represented a major setback since the Germans now faced the two-front war that they had sought to avoid. The war of maneuver was now a war of position with both sides digging trenches and a stalemate settled on the Western Front. This would last till the final months of war despite numerous attempts to force a result and break the deadlock, all at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives.

War On Both Fronts

The failure of the Schlieffen plan had brought a change in the top of the military command, with Erick von Falkenhayn replacing Helmuth von Moltke. This also brought a change in war plans. Germany had tasted success on the eastern front with the spectacular victory at Tannenberg. The aim now was to further weaken Russia such that German armies could again concentrate on fighting the enemy in the west.

In 1915, a combined German and Austro-Hungarian offensive in the summer drove the Russians out of Galicia, and later, out of Russian Poland. Same year, in the west, numerous attacks were launched against German defensive positions but failed. October 1915 saw more success as another joint operation with Austria Hungary led to the conquest of Serbia and the rail network to the Ottoman capital became a reality. The German naval campaign never really took off in the war. However, it was compensated with success in the unrestricted submarine campaign sinking many Allied ships. Problems cropped up after the sinking of Lusitania in May 1915 and Germany was forced to suspend unrestricted U-boat warfare for fear of bringing the United States into the war in the Allied camp.

1916 saw pressures mounting on both fronts as the Allies agreed on simultaneous attacks on all fronts. Fierce fighting ensued at the battles of Verdun and Somme on the Western Front. Falkenhayn’s battle of attrition and German assault at Verdun put the French under pressure but failed to achieve any decisive results ultimately leading to his removal as Commander-in-Chief. The British had relative success at Somme but the Western Front remained in a deadlock. Both the battles had resulted in close to a million German casualties putting the country under tremendous social and military stress. With Germany under pressure in the west, the Russians launched the Brusilov Offensive in June 1916, gaining tremendous success and reclaiming some of the territory lost in 1915. The Royal Navy of Britain continued to cancel out the threat of Germany’s battleships, leaving U-boat warfare as the only alternative.

By 1917, the dual leadership of Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy Erich Ludendorff was at the helm of military affairs in Germany. The enthusiasm for war was fading with the enormous numbers of casualties and the mounting socio-economic difficulties. Thus, the growing voices of antiwar left wing became a concern. The leadership responded to the pressure surrounding the German military effort not by seeking a compromise peace but, on the contrary, by demanding a victorious peace that would make German domination in Europe permanent. Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed despite the American threat, to squeeze the British into capitulation before the Americans arrived in numbers.

The French were in disarray after the failure of the Nivelle Offensive, the Italians had lost to German and Austro Hungarian forces at Caporetto and, on the Eastern front, the Russian Revolutions ensured that the exit of Russia by the end of the year. Morale had returned and was at its greatest since 1914. The German people braced for what Ludendorff said would be the “Peace Offensive” in the west.

Behind the Lines

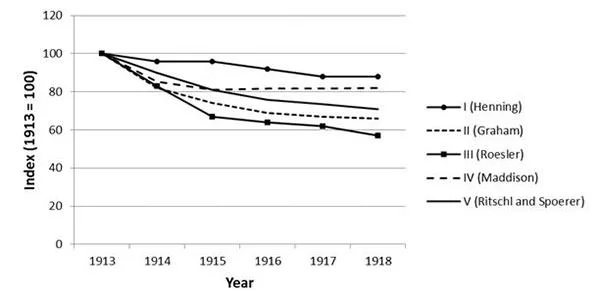

Few had expected a long war in Germany and, since the outbreak of war, debates regarding the political and territorial aims that would follow victory were common among its citizens. In late 1914 the country was short of munitions and steps were taken to reshape the economy in case of a long war. As the war prolonged, the GDP fell, dropping to 76 percent of 1913 levels in 1917.

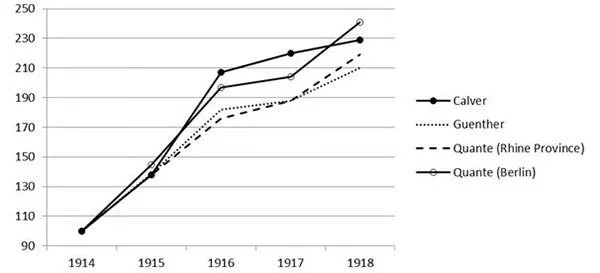

Agriculture was especially hard hit, with output at 60 percent of its pre-war levels in 1917-18. Moreover, the British naval blockade ensured that it was difficult to compensate for reduced food production by imports. Consumption was reduced to about 50 percent of its normal level through the introduction of a system of food rationing. Illness and death due to food shortages occurred every day in the final two years of the war. Hunger protests and strikes began in April 1917 and again more vigorously in January 1918, which was joined by half a million people. A state of emergency had to be declared and the strike leaders were arrested.

There was widespread exhaustion and war-weariness after three years of war and morale had reached an all-time low by the end of 1916. This gave a rise to anti-war left wing voices which were a cause of concern and dealt with prompt action. The loss of soldiers was more and more seen as a personal loss. Moreover, despite efforts, there was a reduction in family incomes generally, especially for war widows. Like in most other European countries contribution made by women was decisive for the functioning of wartime society in Germany, as they stepped out and took up more work outside their households.

German Spring Offensive and Loss In WW1

The armistice with Russia in late 1917 had freed 48 German divisions on the Eastern Front, prompting Germany to consider breaking the deadlock on the Western Front in France. They were aware that their best chance of victory lay in decisive victory before the arrival of overwhelming American forces and supplies. The German Spring Offensive, or the Ludendorff Offensive, was thus launched on March 21, 1918. Code-named Michael, Georgette, Gneisenau and Blücher-Yorck; the operation used Stormtrooper tactics and succeeded in achieving the biggest breakthrough since the initial months of 1914. However, after spectacular success in the beginning, the Spring Offensive faded out as the Germans were unable to move supplies and reinforcements fast enough to maintain their advance, thus exhausting their forces. By June 2018, almost 230,000 men were lost and Allies had managed to defend strategic areas by concentrating their strength.

Another battle at Marne marked the turning point in July and was followed by the 100 Days Allied Offensive starting with the Battle of Amiens. Now bolstered by fresh American Forces, the Allies under the joint command of Ferdinand Foch pushed the Germans back to the Hindenburg line, which were 6 defensive lines, 5 kms deep and parallel to the Belgium border. The line was breached by the end of September and throughout October, German forces found themselves retreating through territory gained in 1914, finally surrendering on November 11, 1918.

Treaty of Versailles

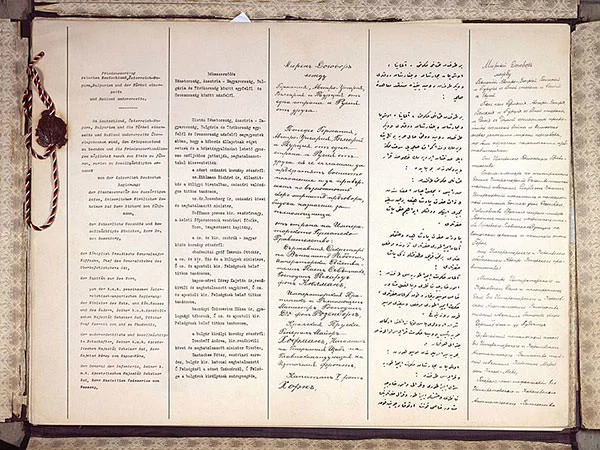

The German surrender in 1918 led to the Treaty of Versailles which ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. The treaty demanded Germany to accept the blame for all the loss and destruction caused during the war. This article, Article 231, later became known as the War Guilt clause. 13 percent of Germany’s European territory was taken away and it was required to renounce sovereignty over its former colonies, which came under Allied control in the League of Nations mandates. The treaty reduced Germany’s armed forces to very low levels and prohibited Germany from possessing certain classes of weapons.

Moreover, Germany was forced into accepting to pay $31.4 billion (£6.6 billion, roughly equivalent to US$442 billion or UK£284 billion in 2019) as reparations to certain countries belonging to the Entente powers. These enormous charges led to hyperinflation and massive unemployment in the country. The humiliation of the treaty and the economic woes it brought led to the rise of the National Socialists (Nazis) in Germany, which in turn, led to World War II.